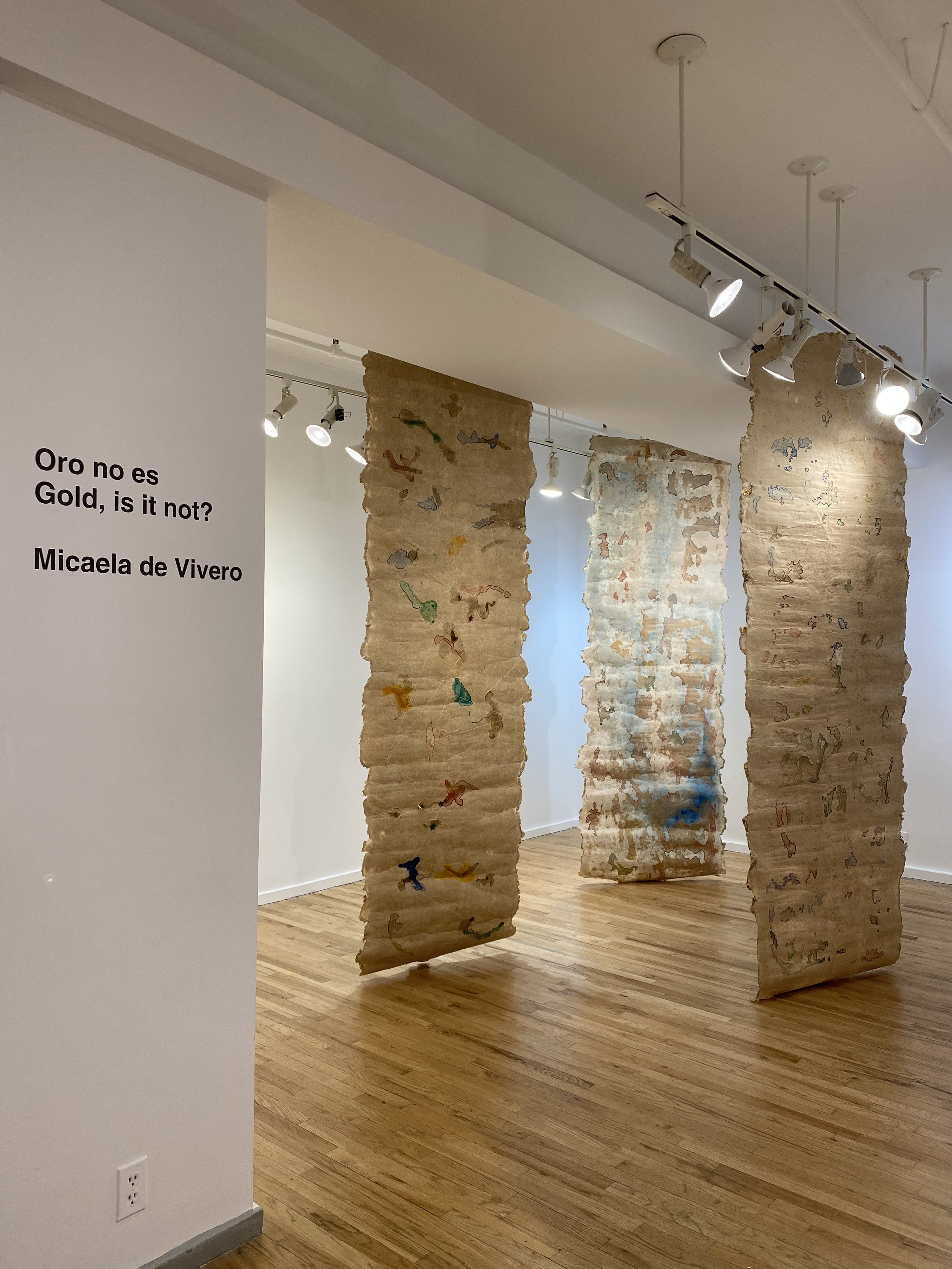

Oro no es/Gold, is it not?

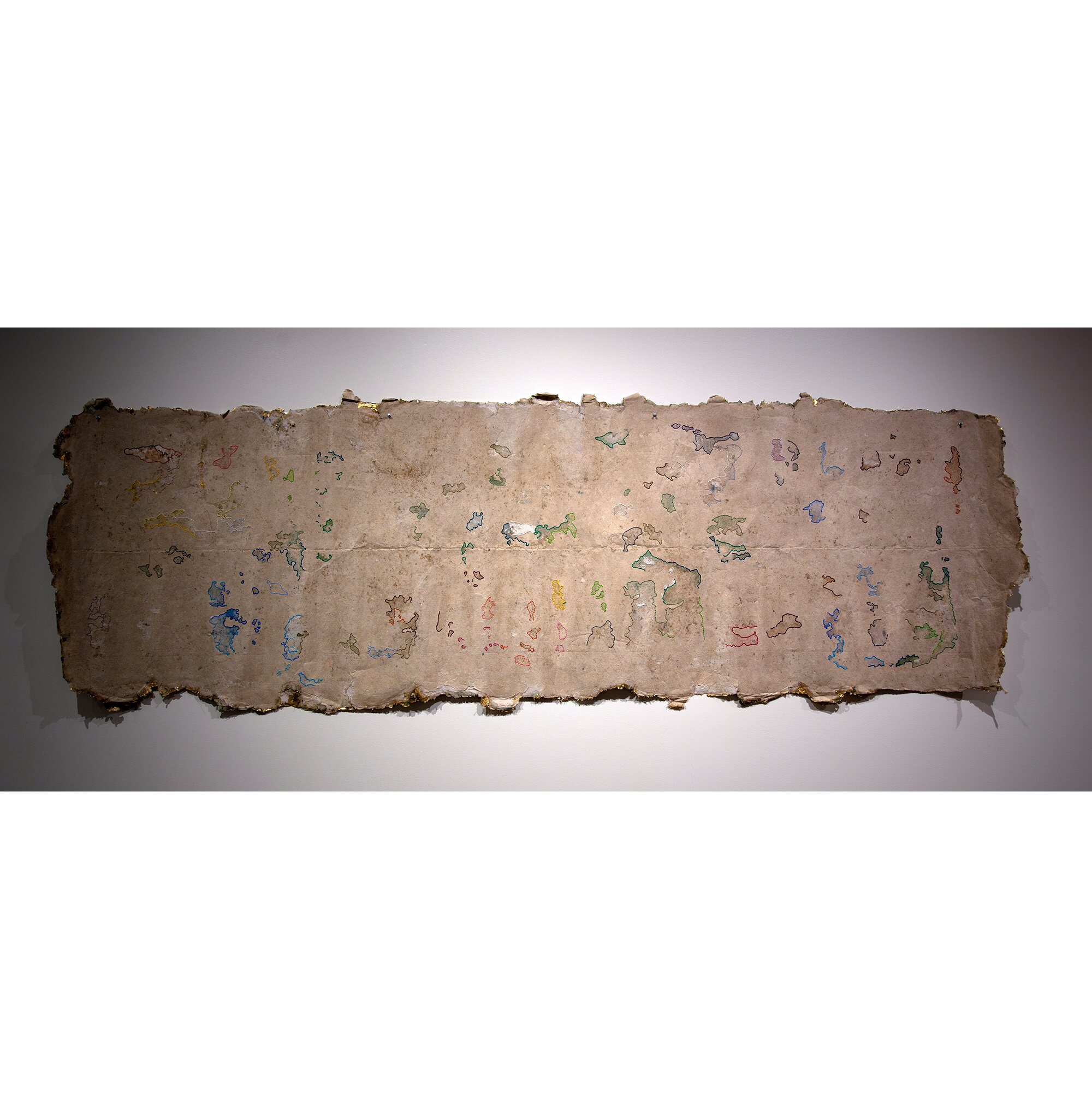

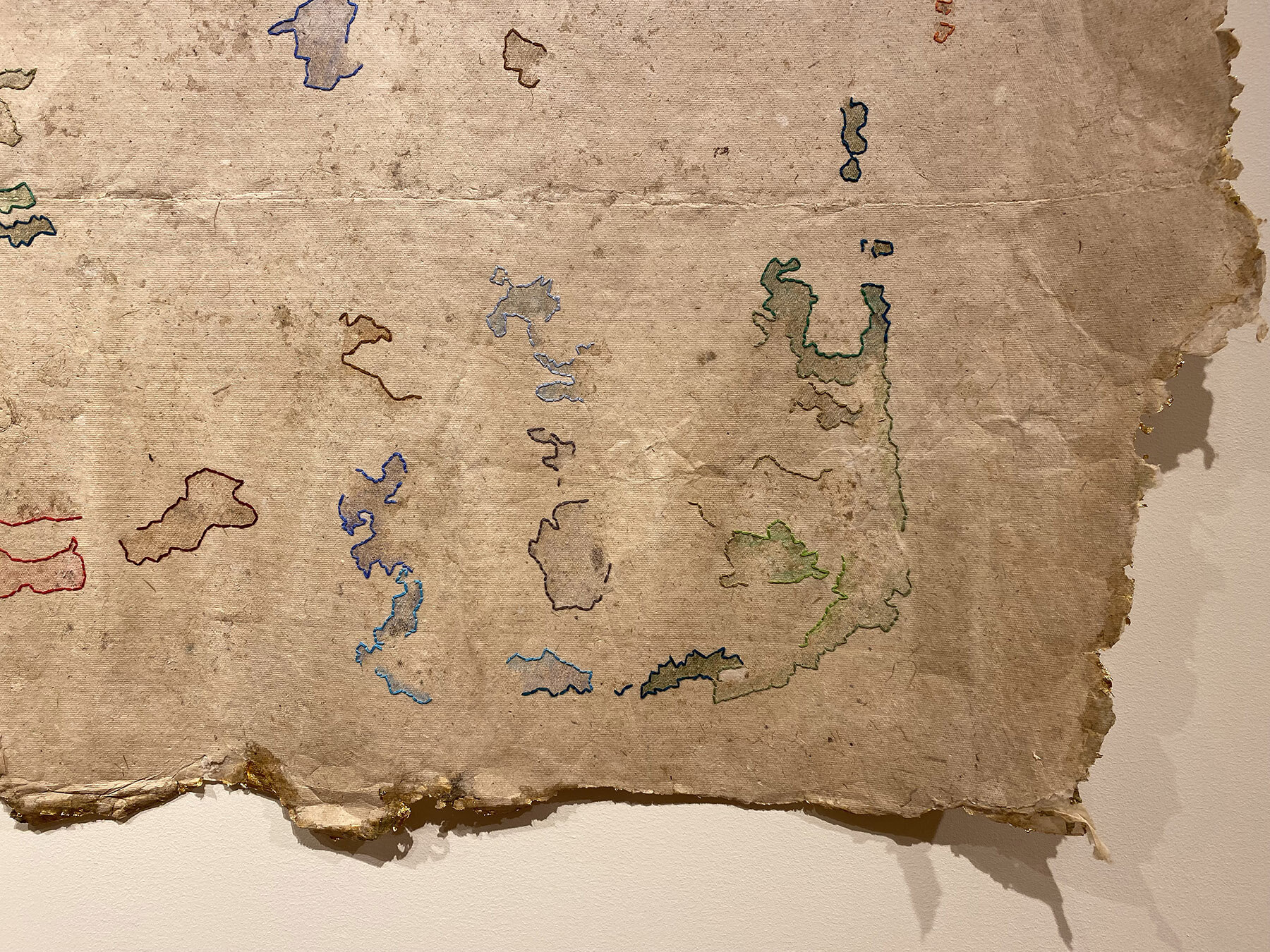

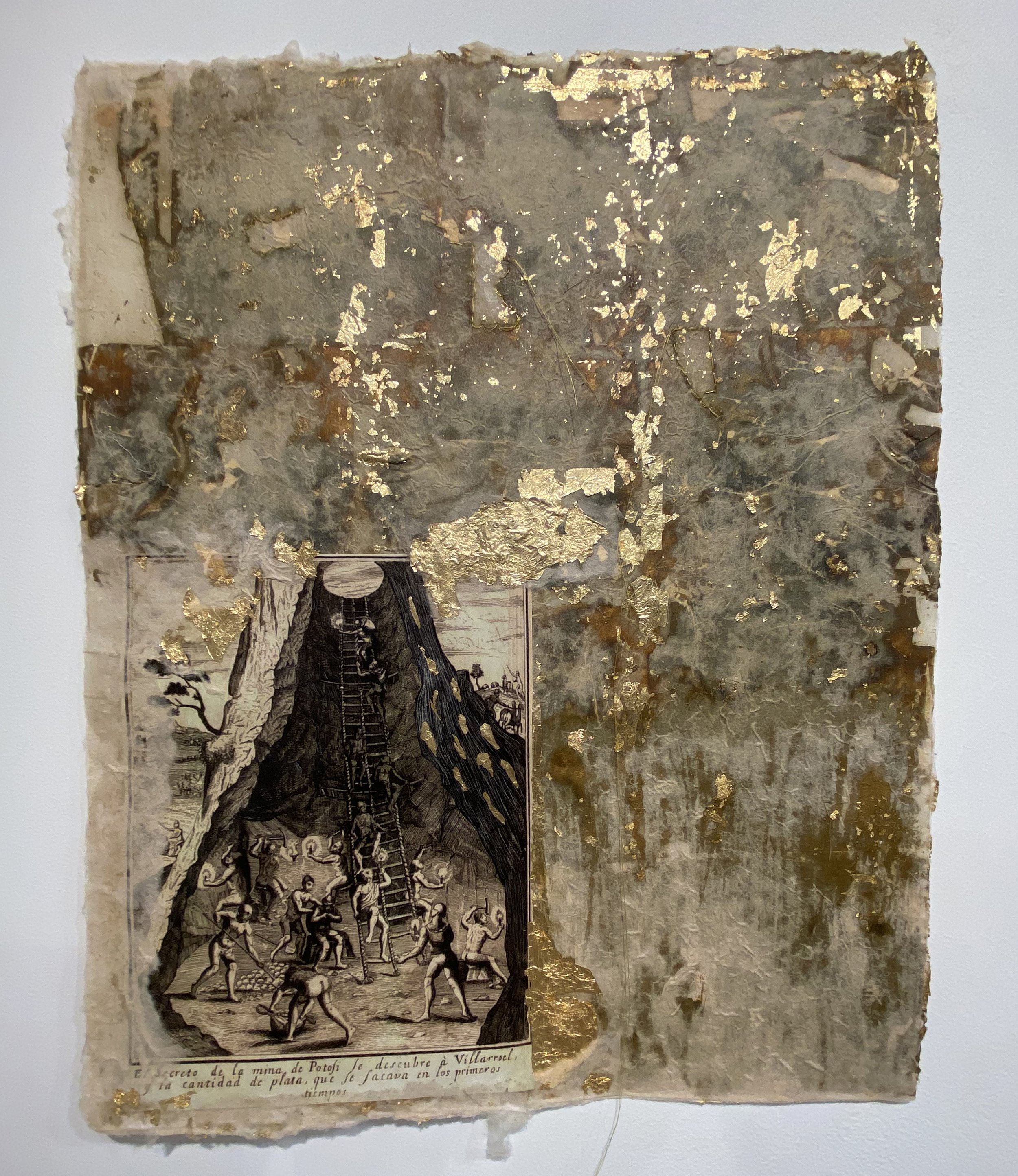

This is a large map-like mural with a surface degraded by cracks, breaks, and holes: it does not pretend to be the pristine or cartographically correct map that von Humboldt might have produced. His purpose was to try to contain an unruly, messy, inchoate world that he could barely comprehend in a neatly ordered map bound up within a rectilinear frame. Vivero presents something closer to reality: her map is more anxious, chaotic, and is rent by fissures revealing fractured glimpses of the unknown. She has broken with the idea of a map’s “key” and denies logical information or “routes” of knowledge. Rather she allows small, isolated images to break through periodically across the map to amplify or to redirect meaning. She has indicated areas where there may be gold by adding glittering seams within the map itself and surrounding it, but her map is ragged and unbounded, as if neither the place nor its people nor possessions will be contained or are containable. The gold is a hint and a promise, an illusion. In fact, it is not gold at all: it is copper-leaf. Gold does not tarnish and this “gold” has tarnished and gone green in parts, as Vivero intended. Vivero wants the tarnish of age on her map: she wants to suggest that sometimes the fulfillment of the promise is more complicated than it at first appears. Vivero seems to suggest that early maps of uncharted terrain functioned as symbolic gestural representations of something more valuable in the minds of the makers than the place itself. The allusion to “treasure” (by the gold) gave the map greater propagandistic significance when it promised a land of great wealth. Thus, maps became visual signifiers of rampant colonial desire. Vivero’s flashes of mock-gold leaf hint at potential treasure, but the portions of deliberately poorly crafted, marred, and uneven paper surface seem to contradict that expectation. Vivero explained this tension as follows: it is like the Guano Islands Act (1856) that allowed the United Stated to take possession of any unclaimed island that contained significant deposits of bird guano—an erstwhile useless substance that was transformed into “treasure” into the 1840s as a source of saltpeter for gunpowder and fertilizer. Of the almost 100 islands claimed most have been “given back” because guano is no longer needed. What we want today we might discard tomorrow. She suggests there is much more value embedded within her map than the (fake) gold that attracts, but we can only comprehend (or see) it if it is of value to us. We might see a very different map if we could “delink” ourselves from our Eurocentric vision.

(Excerpt from writing by Joy Sperling for exhibition at Gallery 310 at Marietta College, Ohio, USA)

Contested Territories

In Contested Territories, a large multi paper mural, Vivero extends this narrative to focus specifically on mapping as a symbolic act of possession. The surface of Contested Territories is punctuated by a series of open-ended forms that are partly drawn with thread on the surface of hand-made paper and partly painted in washes of soft colors. These forms appear like incomplete islands or as islands that appear to rise from the ocean and fall back into it with tidal changes or climate change. They suggest the fleeting nature of territorial possession and, by extension, colonial power in geological history. Once again, Vivero asks the viewer to consider the complicated and many-layered question of possession and power and the hubris of claiming sovereignty over “undiscovered” land and its indigenous people. The map is edged in (fake) gold; its rough outline and natural-colored paper suggest an old, long surviving, or valuable map that has some significance. There is no key to any of Vivero’s maps. Nothing within them is identified—their meaning is encoded, hidden, and deferred. Yet, we sense that these maps are about acquisition and repression: the presence of gold robs them of their innocence and thrusts them into the Western orbit in which money (in the form of gold) equals power. Today, more than ever, we associate gold with power, aggression, and display (often ostentatious displays of power in the form of conspicuous consumption). Even the color gold has been debased. Too much gold feels gaudy, excessive, and unreal. Perhaps that is why it is important to her that her gold is not real: it tarnishes, it is half hidden, and it is intimately just copper, which may have high use-value but has very low exchange-value.

(Excerpt from writing by Joy Sperling)

solo exhibition at Ceres Gallery in New York City

Hand-made paper using abaca or flax paper pulp with gold-leaf. Mixed-media added in order of appearance: watercolor paper with acrylic ink, embroidery, historic prints by Theodor de Bry 1613, text from various sources from the internet, prints of gold artifacts of Pre-Colombian people of current Ecuador, and photograph.